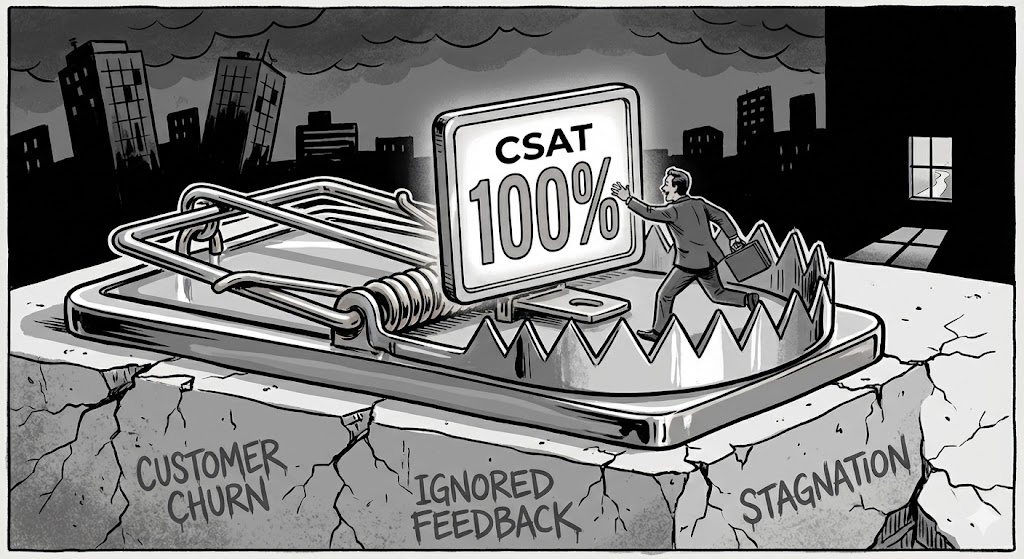

When High CSAT Means You’re Failing

There’s a dashboard somewhere right now showing a perfect row of green numbers. CSAT scores trending upward. Targets exceeded. Leadership pleased. Someone’s probably getting a bonus based on those numbers.

And the customers? They’re quietly leaving.

I’ve seen this pattern enough times now that it’s stopped surprising me. A support team with exemplary satisfaction scores, the kind that get featured in company all-hands, whilst renewal rates slide and product usage stagnates. The metrics say one thing. The reality whispers something else entirely.

The uncomfortable truth is this: sometimes your highest CSAT scores are telling you that you’re solving the wrong problems beautifully.

The Comfort Zone Paradox

Here’s what excellent CSAT often actually measures: your team’s ability to make people feel good about problems they shouldn’t be having in the first place.

Think about it. When does a customer give you a perfect score? Usually when you’ve solved their problem quickly, empathetically, and thoroughly. You’ve turned their frustration into relief. You’ve been responsive, clear, and helpful. By every measure of traditional customer service, you’ve succeeded.

But step back for a moment. Why were they contacting you at all?

If your CSAT is consistently high, it might mean you’ve built an exceptional team at handling support requests. Or it might mean you’ve built an exceptional team at handling the same support requests, over and over again, without anyone noticing that the requests themselves are the problem.

High satisfaction scores can become a numbing agent. They tell you you’re doing well whilst masking the fact that “doing well” has become your ceiling rather than your foundation. You’re optimising for recovery, not prevention. For remediation, not resolution. For making people happy about failure, rather than eliminating the failures entirely.

The Customers Who Never Complain

The truly insidious part is this: your happiest customers in support might be your least valuable customers to your business.

I don’t mean that callously. I mean it structurally. The customers who contact support frequently, get great service, leave high CSAT scores, and return the following week with another question—they’re often not the customers driving your product forward. They’re not the power users uncovering edge cases. They’re not pushing boundaries or scaling usage. They’re maintaining, not growing.

Meanwhile, your most strategically important customers—the ones whose success actually matters to your company’s future—might never appear in your CSAT data at all. Either because they’ve worked around your product’s limitations without telling you, or because they’ve quietly churned after a mediocre support experience that scored a polite 4 out of 5.

The customers who give you perfect scores are often the ones who had low expectations to begin with. They’re delighted you answered. They’re thrilled you cared. They’re not demanding better because they didn’t expect better.

And that should terrify you.

The Vanity Mirror

CSAT has become support’s vanity mirror. It reflects what we want to see—validation, appreciation, evidence of competence. It doesn’t show us what we need to see—the strategic gaps, the systemic failures, the opportunities we’re missing whilst we’re busy being nice.

I’ve watched teams spend hours analysing why their CSAT dropped from 96% to 94%, agonising over every detractor, implementing new coaching programmes and revised macros. Meanwhile, nobody’s asking why 30% of this month’s tickets are about the same three onboarding issues. Nobody’s measuring how many customers gave up before they even contacted support. Nobody’s tracking whether “satisfied” customers are actually succeeding with the product.

The metric has become the mission. We’ve stopped asking what good support actually achieves and started asking how we can make the number go up.

What We Should Be Measuring Instead

If high CSAT can mean you’re failing, what would success actually look like?

Customer capability, for one. Can they do more with your product after interacting with you than they could before? Not just solve their immediate problem, but genuinely increase their competence and autonomy?

Problem elimination, not just problem resolution. Are you tracking the requests that stop coming? The questions that become unnecessary? The friction that gets designed out of the experience entirely?

Strategic impact. Are you helping your most important customers succeed at their most important goals? Or are you distributing your energy democratically across whoever happens to contact you, regardless of strategic value?

These things are harder to measure than CSAT. They don’t fit neatly into dashboards. They require judgement, context, and an acknowledgement that not all customers or interactions are equally valuable. They’re uncomfortable metrics for organisations that prefer clean numbers and clear targets.

But they’re honest.

The Harder Conversation

Here’s what makes this genuinely difficult: your team might be doing excellent work. They might be empathetic, skilled, dedicated professionals who care deeply about helping people. Their high CSAT scores might be entirely deserved based on the interactions they’re having.

The problem isn’t them. The problem is that we’ve asked them to optimise for the wrong outcome.

When support teams are measured primarily on CSAT, they rationally focus on the things that improve CSAT—response time, tone, resolution quality. These aren’t bad things. But they’re insufficient things. They create a support culture that’s reactive and transactional rather than strategic and transformative.

The truly uncomfortable question is whether your support organisation exists to make customers feel good about contacting you, or to make contacting you increasingly unnecessary.

The Signal in the Noise

I’m not suggesting CSAT is meaningless. A dramatic drop in satisfaction scores is absolutely a signal worth investigating. Consistently low scores from a particular customer segment or product area deserve attention.

But excellent CSAT? That’s not a signal. That’s potentially noise, drowning out the signals you actually need to hear.

The next time you see those green numbers trending upward, ask yourself: what aren’t we seeing? What problems are we solving so efficiently that we’ve stopped questioning whether they should exist? Which customers aren’t in this data at all, and what does their absence tell us?

Your high CSAT might be real. Your team might genuinely be doing exceptional work at the thing you’ve asked them to do.

The question is whether you’ve asked them to do the right thing.

Because sometimes the most dangerous number on your dashboard is the one that’s exactly where you want it to be.

What metrics are you tracking that might be hiding more than they reveal? I’d be interested to hear what you’ve replaced or reconsidered in your own organisations.